Arnold Schwarzenegger: The Hero of Perfected Mass

This article, written by Abe Peck, first appeared in Rolling Stone magazine (214) on June 3rd, 1976

Outside the hotel Burgers Park, in Pretoria, South Africa, a group of black workmen in baggy pants and clean white shirts form a circle and drink bootleg “Zulu beer” from brown paper containers. A few feet farther on, a line of black women, kerchiefs on their heads and flowing dresses masking their bodies, wait for “Nie-blanke” (nonwhite) buses to take them to houseclean for white people. Across the street, urchins in scuffed shoes sell newspapers that scream about the hard rain falling in Angola and the soft kiss that Liz Taylor had given her black chauffeur.

But on the enclosed lawn at the Burgers Park hotel, there’s a completely different reality. You might even call it a universe of its own.

It looks like a publicity shot from Spartacus. Large-muscled men lounge motionless, basking in the warm sun that marks spring south of the equator. At an outdoor dining room table, Frank Zane, in one world a Southern California schoolteacher, opens a cellophane envelope and swallows a rainbow — a percentage of the 200 to 400 vitamin/protein pills that will be his “food” for the day. A few tables away, Ken Waller, fresh from the gym, sheepishly explains that he can almost hear his calves talking to him after a workout. Nearby, Robbie Robinson, the current AABA Mr. America and a black sprinter and football player from Florida, examines the deep crevices in his right forearm, then walks through the lobby. He’s staying at this hotel, immune from apartheid, courtesy of the South African Ministry of Sports. Banned from the Olympics for its racist policies, South Africa has put several hundred thousand dollars into the Mr. Universe and Mr. Olympia contests to involve itself in the world sports community.

Zane, Waller and Robinson are only three of the more than 400 men who’ve flown to South Africa from 30-odd countries to compete in these contests, acknowledged as the Super Bowl of bodybuilding. Many hold records for the weight they’ve been able to lift. But, for much of the past year, they’ve spent six hours a day, six days a week — lifting up to 40 tons daily — trying to shape their physical selves according to a shared vision of what the male body should look like.

They don’t think of it as a beauty contest: there’s work, and power, involved in what they do. But some months from now, three of the most developed men here will appear at the Whitney Museum in New York. In a roomful of statues, before a panel of art historians and 2500 onlookers, they’ll flex their muscles and suggest similarities to the alabaster and marble around them. Some of the historians will call the exhibition “campy.” Some audience members will slap their foreheads and call it “gross.” Others, like the men and women in T. S. Eliot’s “Prufrock,” will “come and go, speaking of Michelangelo.”

If Michelangelo came here and saw the people at the pool, he might say . . . a-ha!” observes Franco Columbu, the 5’5″, 185-pound Sardinian Sampson of the muscle magazines. At 32, Columbu’s been Mr. Italy, Mr. Europe and three times each the Mr. World and Mr. Universe of the International Federation of Bodybuilders, the major organization of its kind, and the group sponsoring this South African contest. Columbu is a professional who makes perhaps $50,000 a year from endorsements, mail-order products and competitions. In 1975, he finished second in the Olympia contest. He has no illusions about his body:

“This is not a normal thing. We have the muscles developed to the maximum, trying to win a contest. Muscles developed the way we’re developed — that’s abnormal. We are too developed.”

Columbu, like the others, is a specialist at anabolizing his muscles — tearing them down by “bombing them” with concentrated exercise, then supplying them with huge amounts of protein (including artificial steroids) while they’re resting to make them grow.

But big is not enough. Columbu’s muscles must form sweeping peaks and deep valleys. Each has to be exercised — bench presses for the chest, calf raises for the legs, squats and curls and rows for the rest — to make sure that growth is proportional. They have to move fluidly when displayed in front of the practice mirror. And they have to be ready for the 90 seconds that he’ll spend, oiled and hairless, onstage, trying to become Mr. Olympia, the professional who’s the best bodybuilder in the world.

To do that, though, Columbu will have to beat Arnold Schwarzenegger, the hero of perfected mass.

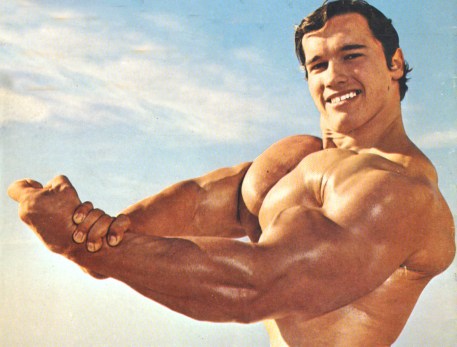

Lying on a towel he has placed squarely in the center of the patio, Arnold Schwarzenegger (the name means “black plow man” in Austrian) watches the other bodybuilders quietly sunbathing or boisterously hoisting some local girls over their heads. Even in the present company, he looks unusual. His 6’2″, 235-pound body tapers from a massive 57-inch chest past back muscles only wet-dreamed by Mr. Universes of the protein-scarce 1940s, then swirls its way into a streamlined waist. His calves are upside-down hearts. His biceps look like carved softballs. His back muscles have been scooped out by a cookie cutter working overtime. Two days ago, he ended a TV interview by blinking his pectoral muscles goodbye, and the far-from-little devils are still jumping around his chest like kangaroos on methedrine.

The muscle magazines call him “the Austrian Oak” — one look at his last name and everybody else calls him Arnold. According to Charles Gaines, who wrote the text for Pumping Iron, the word-and-picture book that legitimized interest in “the art and sport of bodybuilding” among people who hadn’t known a tricep from a tricycle: “The thing that makes Arnold unique is not only that he’s big. Every single part on Arnold is perfect, from his ankles all the way down to his wrists and his fingers. You see him move and you don’t see a single flawed relationship of one thing to another.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger’s been Mr. Universe five different times, and Mr. Olympia since 1970. He hasn’t lost a bodybuilding contest in eight years and, at 28, he makes $100,000 a year from posing at and promoting exhibitions, and from endorsements, investments, and the sale of books and devices designed to help develop muscles. He’s been given extensive play in the media. Two spreads in People. A photojournalism story by Candice Bergen on the Today show. The Pumping Iron documentary that George Butler, the man who took the photos for the book, has come to South Africa to direct. A major role in Bob Rafelson’s Hollywood production of Stay Hungry, the film adaptation of Gaines’s novel about a patrician Southerner’s encounter with the candid, immediate world of bodybuilding.

Arnold is on the lawn for the final part of his training. He’s exercised, eaten and slept, and now he’s tanning his skin to the tone that will give his muscles their best finish under the lights at the University of South Africa auditorium across town. It’s not exactly hard work, but he’s repeatedly interrupted by a stream of visitors. A burly father brings his son up for an autograph. Second-string competitors come by to introduce themselves. One Mr. Universe contender, his chest looking like a huge, pleated accordion, even asks, “Hey Arnold, should I eat a piece of fruit or a piece of toast for breakfast?”

There’s a scene that may appear in Pumping Iron which sums all this up. Arnold and a group of worldclass bodybuilders are posing at “Muscle Rock,” in Venice, California. As they demonstrate their poses and muscles, Arnold moves to the center, a little above the rest. Now he explains why he thinks he belonged there: “I feel you only can have a few leaders,” he says in a guttural, confident voice, “and then the rest is followers. I feel that I am the born leader and that I’ve always impressed with being the leader. I hate to be the follower. I had this when I was a little boy . . . .”

Arnold grew up in Graz, Austria. His mother was a hausfrau; his father, now dead, a policeman who doubled as the European champion at the obscure sport of ice curling. His parents thought he’d be a mechanic or a businessman, and he seemed headed in that direction. Then he had a vision. ”

Around the time of grammar school I had this incredible desire to be recognized. Whenever I watched television or film I always put myself up there on the screen and said, ‘How would it be if people looked at me?’ Why, I don’t know. I got the feeling that I was meant to be more than just an average guy running around, that I was chosen to do something special.

“At that point, I didn’t think about money. I thought about the fame, about just being the greatest. I was dreaming about being some dictator of a country or some savior like Jesus. Just to be recognized.”

After a while, he “just clicked into bodybuilding.” It was a plausible choice for someone addicted to fame. Bodybuilders compete without teammates, without equipment, with only posing trunks between them and their audience. Their presence demands the rapt attention that somebody would give a show of fine horses, and true fans respond with the intensity of a stomp-down rodeo audience. Winner takes all.

“People say to me, ‘Why do you train? Why do you want to get the body perfect? Don’t you know it is more important what you have inside, what you have in your brain?’

“It’s not you. It’s a body, and what you do is look at it as a piece you try to get perfect. It has nothing to do with making yourself perfect, because to make yourself perfect it takes much more than just a body. The number one thing is to be mentally and physically balanced.

“What it boils down to is you become an artist and you’re working on your own body like an artist works on a piece of sculpture. He decides, ‘I think we have to put a little bit more clay on the calves,’ where you just say, ‘I think I have to do ten more sets on my calfwork.’ If you have a good eye for it, you see the faults and you work on it. You can’t look in the mirror and say, ‘I look great.’ You have to be very clinical and just analyze it and work on it.”

But isn’t this egomaniacal?

“What people don’t understand is that the only way you can check your progress is to pose into the mirror and find out how moves go, and if muscles are getting more separated, and if he gets more definition and symmetry, and so on.

“It’s totally mental, the whole trip. I tell you, the mind has to be strong to go through these workouts. I just go for a focused goal that I have in front of me and something drives me there, a special force.

“If you break the pain barrier, that makes you the champion. When it hurts, and when there’s pain while you’re training, that means something positive — growing, success, progress one step closer to winning. So you turn it into pleasure. Pain becomes pleasure without being masochistic.”

At 19, Arnold had been a competitive swimmer, soccer player, skier, boxer, wrestler, shot-putter, javelin thrower and European curling champion. At 19, he worked as an instructor in a gymnasium, where he could check-pose into the mirror and perfect his discipline. At 19, he was quite the merry prankster.

“A guy came in and said he wanted to learn a new technique in posing; the old ones he’d already perfected. So I had him pose for me and the guy looked like an idiot. So I said, ‘Okay, if you think you’re a good poser now, I’m going to make you much better’ — and make you look like a bigger idiot.

“So I told the guy that the new system in posing is to scream while you’re posing. And he said, ‘How does this work?’ And I said, ‘It’s obviously a secret. It’s from America. Whoever does it first in Europe will obviously be the winner of many contests.’

“He got oiled up — a big mess — and I said, ‘The lower your hands are in a pose, the lower you have to scream, and the higher your hands are over your head, the higher you have to scream.'”

He growls —”Oooooh-aaaaiee!” — then goes on.

“The guy said, ‘That sounds kind of impressive. That really will let people know that you’re up there.’ So I trained the guy for two days, and a week later was the Mr. Munich contest. And I told him that he should swear not to tell anybody, because I was afraid somebody would tell him, ‘You’re stupid.'”

He continues, conspiratorially. “So he promises, and the Mr. Munich contest comes around. I told him that he should run out with a loud scream. And he ran out, dripping with oil, and started screaming, ‘Oooooh-aaaaaiee!’ with weird eyes.

“They pulled him off the stage and drove him away. They took it so seriously. He kept screaming, ‘Arnold! Help! They don’t understand me!’ He came back a week later and said, ‘What happened?’ And I said, ‘They weren’t educated enough.’

“I only do that when a guy’s really an asshole. If somebody comes to me and says, ‘Arnold, I really need help,’ I will take the time and sit down with the guy and put him on the program that will definitely help.

“But if somebody comes to me and says, ‘I have the best routine and, as a matter of fact, I’m stronger than you are, and I have bigger arms than you, but I want them to be much bigger . . . How do I do it?’ — then he can be 100% sure that I will fuck him up.”

The Ferrigno family is gathered around the dinner table in their Brooklyn house. Between bites of manicotti, Matty Ferrigno, a retired NYPD lieutenant, leans across the table and tells his 23-year-old son Louie, whom he trains, about a dream he’s had.

“We’re about five minutes away and I start to put the oil on you . . . . And when it gets down to two minutes I start thinkin’ about the cattle goin’ to the slaughter.” Matty pauses for another bite, then continues. “It’s so difficult. I keep wonderin’! Am I gonna embrace ya, or are we gonna go away like beaten dogs?”

Backstage at the University of South Africa, 7500 miles from Brooklyn, Matty and Louie Ferrigno are getting ready for the Olympia.

The preparation room looks like a typical suburban basement: blond wood paneling, a leather couch along one wall, red and black carpeting. The only unusual features are a pennant suggesting Blossom margarine “for health and strength” and an abundance of weights.

“Arrgh!”

At 6’5″ and 280 pounds, Louie has been talked up as someone who can beat Arnold. Now he stoops over and pulls a 180-pound barbell close to his chest with a motion that gives the exercise its name: the bendover row. Each repetition is accompanied by a banshee yell.

But from across the room, Arnold lets it be known that he’s sure of his chances.

“What did you say, Louie?” he says, replying to Ferrigno’s scream. “You make too much noise. It has to be quiet here . . . like in a church.”

Arnold is joking, but there is an adrenalin atmosphere in the room that his final preparations only reinforce. With the Olympia just minutes away, he lays on his back on an exercise bench and begins bodybuilding’s most intimate ritual.

Hefting a pair of 60-pound dumbbells, Arnold begins to pump up.

Taking a deep breath, he arcs the weights off the floor until they click lightly over his chest. Then he swings them back toward the ground. The only sound is a short exhale.

Arnold repeats the exercise, which is called a dumbbell flye, and which he’d previously described as “hugging your girl.” Once — psst. Twice — psst. A few more times. Rhythmically, oxygen-rich blood begins to rush into his upper body. Muscles become hot and pleasant. His chest actually changes shape. The ridges bounding his pectoral muscles sharpen and his veins stand up like filigree on an armored breastplate. It’s the damnest thing.

“You can say a pump is as good as coming with a chick in bed,” he’s said. “To me, a pump is a supreme feeling, as if you were in the desert for two weeks without water and then you get the first gulp of water. That’s what the pump is to me. It’s the ultimate feeling, the feeling every bodybuilder looks forward to.”

Arnold’s pump is also a psyche-out, designed to convince the others that they shouldn’t bother going onstage. Serge Nubret, Mr. Europe, a black man whose stomach muscles are so riffled that they look like a naugahyde file folder, watches Arnold’s chest glisten and stares down at the floor. And when Arnold asks Lou how he expects to do, Ferrigno answers, only half-facetiously, “I will lose, Arnold. You are the best.”

Twenty-four hours ago, the Mr. Universe contest had looked like Matty Ferrigno’s cattle going to slaughter. Some in the army of men padding around the stone and wood floors knew they were just along for the free trip. Others felt like Mike Katz, the huge former New York Jets lineman and current Connecticut schoolteacher. “I would quit, but if I don’t win the Universe, I wouldn’t feel like I’m a man.”

Ken Waller won the Universe. Katz finished fourth. Bad calves.

Today the tyranny of perfection continues. First the under-200-pound class had come down to a contest between Columbu and Ed Corney, a 42-year-old San Jose nightclub owner who’s reputed to be the world’s best poser. Columbu, the more densely muscled man, took it.

Now, Arnold, Nubret and Ferrigno are onstage in the almost empty auditorium for the prejudging that will determine the finalist in the over-200-pound class.

“Strike!” the chief judge says, and the three men move counterclockwise through the six mandatory poses. They hold the front double bicep “shot,” tensing their arms as if their veins contained caffeine instead of blood. Then the side chest, with right arms cradled at hip level to frame the pectoral muscles. They shift into the rear bicep, modifying it into a “lat spread” that flares out the latissimus ‘dorsi muscles of their backs like manta rays. A left chest shot. And then a front lat spread, with stomachs sucked in like a drill sergeant’s dream. The judges make silent appraisals, checking for muscle size, definition, proportion, symmetry — even for veins, which reveal the absence of fat under skin.

Standing quietly before the optional posing, when each contestant tries to maximize his best “parts” and hide his “flaws,” Arnold seems confident. He’s sculpted his body to remove imperfection. He’s watched movies of his opponents. He’s taken ballet lessons to loosen up his posing. He’s even put a few tricks up the sleeve he’s left in the locker room.

“You don’t really push people out of the way,” he explained. “When you see your goal in front of you, the only way you can get there is by walking straight toward it. And whatever happens to be in front of you, those are the things you just cannot look at or be bothered with. Which sometimes is kind of cruel and selfish, but you have no other choice.”

That was his situation, he claimed, in 1970 when he and an extremely muscular Chicago Police Department physical trainer named Sergio Oliva posed down against each other.

“They judged the contest right in front of an audience. So when we had the pose-off, half of the people screamed for him and half for me. I felt: you can’t take the chance; it could go either way. We were posing for around ten minutes, and we were hitting a back pose, and I said, ‘Fuck it, let’s leave.’

“He said, ‘Good enough,’ and just walked off. But he didn’t watch what I was doing, so I stayed there and kept hitting another shot. Then I called him back and said, ‘Sergio, don’t give up.’

“It made him look like an idiot. The Spanish people turned against him. The black people turned against him. The whole hall was screaming, ‘Arnold.'”

Onstage during the optional posing, each man fights a battle between tyranny and humanity. As he becomes a discus thrower, a flickering candle, a neocaveman popping muscles like he’s standing on an electrified grid, the judges deduct points for perceived flaws. As each man contends bodily that what he does is a sport, he confronts the reality that his performance is closer to an actor’s than to a ballplayer’s. An ideal of what it is to be a man is measured by the size of his muscles, and beauty sometimes appears to be only skin-deep.

But George Butler has caught the humanistic side of what’s going on. “Bodybuilding’s taken the simplest thing that mankind has and dealt with it. It deals with the most basic thing which is given to man — his body.”

Arnold lifts that simplicity to a higher level. The tyranny of perfection finds Ferrigno not “cut up” enough and Nubret “too fine.” But in a pose-down with Nubret, Arnold combines the power of a flexed arm with the tenderness of an open palm. And at night, when he competes against Columbu in front of 1000 white South Africans, the screams for him are the loudest. Columbu crouches to put his massive upper body at eye-level and hide the slight bow in his legs. But Arnold kneels and soars, and when he rises behind a bicep move that cuts scythelike upward from the floor, a pose that certifies his winning the 2500 Rand ($3000) first prize, one observer looks past the muscles and sees “the joy and the humor.”

Like Dick Tracy says, “He who controls magnetism controls the universe.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger says that “all the guys are like regular guys on the street.” Back in the States waiting for the next contest, Mr. Universe, Ken Waller, sells used cars in Los Angeles. Frank Zane, a.k.a. the Silver Surfer to some of the media, teaches high school math, and credits his 3.85 average in a grad school psych program to the discipline he learned from bodybuilding. The Sardinian Sampson, known on campus as Franco Columbu, studies at a chiropractic college in Los Angeles. The “world’s best poser,” Ed Corney, cards patrons at the door of his bar.

Arnold’s not waiting. He’s quit competition and gone to Hollywood.

“I wanted to be the best in the world in something. I didn’t really care what at that point. Now I’m more concerned about getting into something else, like acting and business. I stayed 13 years. Why not do something else in the next ten? Maybe I can be great in that.”

“He can come in to our business and work his way up.”

Joe Weider sits by the side of his pool, which features an artificial waterfall and other accouterments of the good life. It’s a hot day in Hollywood and, in the spirit of participatory journalism, we’re tanning our bodies. I’ve come unprepared, so my posing trunks are a pair of jockey briefs. Lordy, Lordy.

Weider’s capsule description of himself begins, “I’m 54, 5’11” and weigh 200 pounds — when I’m in shape I weigh 190.” He looks less like the Herculean drawing that often graces the inside cover of Muscle Builder/Power magazine than a fit patron of a British gambling casino. But make no mistake: over the years Weider’s power has only increased. The Weider complex of corporations, housed in the Weider Building in Woodland Hills, California, includes Joe Weider Health and Fitness, Body Persuasion System Inc. and Weider Communications. They churn out exercise equipment for everyday folk and esoteric products for physical-culture buffs who swear by the “Weider Method” of bodybuilding. His magazines sell 250,000 copies a month. He has business arrangements with corporations all over the world. His brother Ben heads the International Federation of Bodybuilders, and the jurisdictional disputes over who would represent the American team in South Africa included innuendoes of Joe Weider’s influence from afar.

Weider fought his way out of the Jewish ghetto of French-Canadian Montreal, and short bits of philosophy spurt from his mouth like multiaccented machine-gun bullets. Bodybuilding isn’t purposeless: “What’s the purpose of climbing a mountain?” It puts you “in tune with life” and makes it unnecessary to “go to institutes and touch people and go through all that sickness.” Homosexuals covet bodybuilders, but bodybuilders aren’t homosexuals. The proof: “The women they’ve married all have big boobs. You go to Arnold’s parties, you see girls with big breasts.”

Joe Weider brought Arnold to America. “He was in Europe,” Weider says, “and I had one of our agents overseas speak to him in London, to come over here to compete in our contest in Florida. If he would come here I would pay his expenses. And while he was under the lights, I’d be able to see if he had what it takes to become a great champion. A lot of people have great bodies and great potential. I just wanted to see if he had the willpower, the determination, the ability to concentrate into his training the ferociousness that would bring back all the results.”

Arnold lost the 1968 Mr. Universe contest to Frank Zane, but Weider was impressed. “He had great mass but he didn’t have perfect proportion and his body didn’t have the all-around beauty that this other fellow had. He was a fairly good poser — not as great as he thought — but I worked out with him and I knew he really had the fire. I had him come out to California and train and have a free mind and devote himself to the sport.

“We gave him a lot of publicity, promoted him, we made the world aware.” The arrangement has had mutual benefits: in one issue of Muscle Builder/Power magazine, Arnold endorsed the following: Mr. America Home Gym Training Outfit, Arnold’s Super-Arm Blaster/Kambered Kurling Bar (twice each), Weider protein supplements and Joe Weider’s “‘Wildcat’ Protein Powerizers,” a Weight Support Belt, Joe Weider’s “World’s Most Powerful Lifting Belts,” a house ad for the magazine, an ad for one or all of nine “‘Arnold Strong’ shortcuts to massive muscularity” booklets, and “The Arnold Photo Album.” He was also the featured subject of “Arnold on Location,” a story about the filming of Stay Hungry. And he hosted an “Ask the Champ” column.

Eighteen pages of ads. Two pages of stories. A column. It’s way ahead of working the night shift at the factory.

Weider and Arnold have an interesting relationship. Arnold calls him a “father image and in some ways an idol . . .” and does a great imitation of his voice. Weider talks about Arnold’s “willpower,” “ferociousness of purpose” and “sensitivity toward people,” but paternally suggests that Arnold will have to decide between competition, movies and business. “You can’t serve two masters and get to the top. You can’t be a jack of all trades.” Still, Weider has no doubts about Arnold’s success. “His future will be based on his intelligence. It’s a very bright future.”

In San Jose, California, some time later, it becomes clear that Arnold can fly under his own power. The 3100-seat Center for the Performing Arts is sold out for the Mr. Western America show that Arnold is coproducing. The atmosphere is like a classical music concert — as the bodybuilders pose among Ionic columns, the audience remains strangely silent. Backstage, the casually dressed Arnold works the sound board, boosting the rock and jazz tape, collaged by San Francisco songwriter Ron Nagle, which complements “Exodus,” the traditional posing song.

Arnold gets local favorite Ed Corney, Ken Waller, Robbie Robinson, Franco Columbu and Frank Zane onto the stage and gives a brief exhibition himself. George Butler shows 20 minutes of Pumping Iron, which is as intense as Endless Summer on a large screen. The show isn’t epic, but it’s professional enough that Arnold will have no trouble if he decides to barnstorm across the country.

Amid the half-naked bodies padding around backstage, one man in a dapper suit stands off to one side, smiling. Joe Weider has come to pay his respects. His deliberate low profile validates Arnold’s estimation of their relationship. “He has a lot of influence on my life because I let him have influence in my life.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger made his movie debut in Hercules in New York, an unreleased 1970 film that starred skinny comedian Arnold Stang and recent immigrant “Arnold Strong.” Now, on the screen at Harold Schneider and Bob Rafelson’s Outov Inc., the Hollywood production of Stay Hungry is about to preview.

As the film unfolds, it becomes clear that director/co-producer Rafelson, who brought us Five Easy Pieces and The King of Marvin Gardens, has focused more on the grotesqueries of the South than on the world (including its grotesqueries) of bodybuilding. Competition shots are minimized, and bodybuilding goes unexplained. Clothed for almost the entire movie, Arnold is forced to rely on his thespianship instead of his triceps.

“Long before I sent Arnold to acting school,” Rafelson had said earlier, “I told him it would be an ordeal and that he would be displaced from being Number One in the Universe to being just another actor.”

Sure enough, Arnold found the transition to be “a mind-blower. I’d been in an atmosphere for so many years where whatever I said was right. And you get used to that, and your ego gets built up so much.

“When I took some acting lessons and somebody said, ‘No, do this over,’ or ‘Arnold, this wasn’t good,’ I took it very personally — like I wasn’t good. It was kind of a blow. I had to let everything go. It was like surrendering everything I had and saying, ‘Okay, let’s start from the beginning. You’re nothing here. You’re just a beginner. You’re just a little punk around these actors. You’re just shit.'”

Rafelson recalls that Arnold was deeply affected by his new situation. “He had nightmares that I would call him in the office and say, ‘C’mon Arnold, let’s start working,’ and the lights would be off, and he would be evaluated by a faceless person.”

But Arnold rallied. “How did I win Mr. Universe? I won it because I had confidence in what I was doing. I had no negative attitude about it. I set my goal and then went for it without even questioning whether I could do it or not. You apply it so that it makes you more successful in everything else.”

He worked hard, made an honesty pact with Bridges, and opened himself up to criticism at after-shooting cast sessions. He even surrendered control of his body to Rafelson, who ordered him to lose 30 pounds so he wouldn’t dwarf black-sheep rich kid Craig Blake (Jeff Bridges) and salty country girl Mary Tate Farnsworth (Sally Field).

“What was he working on for all this while?” Rafelson asks rhetorically. “He looks like a 6’2″, 190-pound guy. When he undresses for the Universe contest, it’s at a powerful emotional moment. When people see it, there’s a gasp. The camera frames the shot, and Arnold is just stupendous.”

On the screen it’s obvious that, though it’ll be a while before Arnold stands on the Number One platform at the Oscar ceremony, he’s definitely broken the beefcake barrier. As Joe Santo, Mr. Austria, he plays a fiddle (proving it by holding a note longer than the good ol’ boys around him). He convincingly dissertates on cut glass and expresses his real-life yearning to stay hungry for the next experience. He’s good enough for Rafelson to say, “I really think he can play a whole range of parts.”

And what did Rafelson see in Arnold when he wasn’t framing his body in the camera?

“I don’t think it’s what you do in life, but the satisfaction that’s derived from it,” Rafelson said. “Arnold represents somebody who is deeply satisfied.”

Springtime in California, and Arnold sits comfortably on a couch in his Santa Monica house. The record on top of the pile near the stereo isn’t “You’re So Vain” or Alvin Lee’s Pump Iron, but Art Garfunkel’s Breakaway. Three paintings hang under a stairway; one, a softly macho picture of a man cupping a mermaid’s breast, turns out to be a Chagall. Upstairs, an office is filled with neat stacks of Arnold’s muscle-development books. There are no weights in the house: “I don’t keep them here,” Arnold says, making a face.

Earlier that day, Joe Weider had recalled Arnold’s early days in America. “The man came here, he could hardly speak English. He had a very heavy dialect. He didn’t know his way around.” Weider’s prediction of a bright future included a judgment that “he’s the only bodybuilder who had enough intelligence to carry what he has accomplished physically into society.” Weider had said that Arnold was something of the All-American boy — started at the bottom, worked his way up, overcame all sorts of hardships.” Asked about it, Arnold agrees.

“I’m pretty much all that you just said. But I think I’m the All-European boy. It gave me a certain appreciation of this country. This is a gold mine, this is heaven — with the political system and the police system and the whole thing. I mean, over there it’s brutal. It’s a police state. Austria, Germany — there’s no monkey business, and so I appreciate this country because of my upbringing and because there wasn’t much money over there.”

Arnold’s appreciation doesn’t mean that he thinks America is the reason for his success. “The big factor in my drive is only one thing, that I was meant to be something special. What I mean actually is that I have the feeling that I am not an average guy. I have the feeling that I was not born just to die and just to take a shit everyday and to eat, to work, to make money to eat and all that. I was meant to be more — you know, to do revolutionary things, to break records, to just do things that nobody else can do.

“Everybody was talking, I’m going to be a bricklayer, I’m going to be a mechanic, and ‘Arnold, what are you going to be?’ And I said, ‘I don’t know, but I know one thing — I’m not going to be in this country my whole life. I’m going to be in America somewhere. I’m going to be something really great.’ They thought I was sick in the head.

“It started slow. I always kind of looked down on people who did just the regular thing. Like when guys started smoking when they were 11 years old, I was the first to say, ‘No good.’ You know, I felt this was for the untermensch — you know, the low class. And then everybody went out at night and went dancing because there was nothing else to do — not that they enjoyed dancing, but it was just the thing to do. I thought it was stupid. I found they were wasting their time away and their life away instead of doing something more — where they can progress, where they can go on, learning something, doing something with themselves.

“I just always looked at my friends and could never figure out why they go this way. There’s so much more meaning to life than just going through this regular motions and then pass away. My friends now are all married, they have trouble at home, they have children running all over screaming loud. They go to the factory working, and I’m over here and I have a good time.”

Talk drifts back to those little questions you’ve asked all through this article. The answers, culled from locker rooms and living rooms around the world:

• They can move.

• Some are smart.

• It doesn’t turn to fat.

• Women can’t build big ones — probably for lack of testosterone.

• No, but they tell a lot of “fag jokes.”

• All different sizes. The conversation breaks when Reli Schwarzenegger, Arnold’s mother, comes downstairs. Arnold brought her to Santa Monica for an extended vacation, their first one together since she watched him pose in Germany, in 1972.

With Arnold translating over coffee and cake, Mrs. Schwarzenegger says what it was like for her to watch a bodybuilding contest. “She says that when she saw me competing in Essen, she was just thinking back to when I was ten years old and I said I would be the greatest.” Suddenly Arnold laughs hysterically. “She says she proud that as a mother she has such a boy who has such big muscles and stuff, but if she were a young girl she wouldn’t fall for me.”

The ladies’ reactions vary. One good friend, a high, hip lady, is Swept Away. Another, a pretty editorial assistant, calls him “a chauvinist chump.” A third, an aspiring actress, sees Stay Hungry, gasps when Arnold unveils his physique and says, “He’s charming, even with all those muscles.”

Arnold has no complaints. He’s been the best in his field, and he’s verging on success in several others. And he has the politician’s gift, the ability to focus energy so that people think he only has eyes for them.

Still, his remarks recall a film session for Pumping Iron at the Pretoria Zoo. Walking among the lions and elephants, Charles Gaines, whom Arnold lists as “an idol” because of his balance of mental and physical activity, tried to get him to speak about his emotions. At first, George Butler felt that Arnold was guarded; later he applauded his candor. During our interviews, Arnold’s responses reveal a similar contradiction.

Disappointments: none. Fears: only of “the unknown.” Gentleness: “The stronger and more secure you get, the more you can afford to be gentle and be good to people.” Laughter: “I can turn anything into fun.” Other people’s frustrations: “I think very little about it. Nobody’s thinking about me when I’m frustrated. I have to worry about my own thing.” And security?

“Security,” he says, walking out the door toward the Mercedes 450 parked in his driveway, “means nothing to me. There is no security in the world anymore — that’s been proven over and over. You know what happened to the Japanese people in the second World War. If they bought a house they never got it back again. Look at Germany and the Jewish people. Everything was taken away. There is no security — and so many people are worried about security.

“No, I’m not that worried about security. I think as long as you work on yourself to do something special, and if you’re great, then whatever time you hit — depression, recession or total collapse of a country, you always can do something with yourself. They will always appreciate you if you’re good at something.”

Check that off the list of things I was cousnfed about.

Har du pendla for meg SÃ¥ snilt Tusen takk… Ja, hvis DnB blir tussige, sÃ¥ finnes det da andre banker, jeg vil ikke gi meg for nÃ¥r magefølelsen sier noe sÃ¥ hører jeg etter… Det gjør jeg…For et Ã¥r det har vært – og fortsetter Ã¥ være

Bob, you should have sent me an e-mail about this; we could have made it a jam piece, then have a competition to decide who wins it to get people to look at your weo’cmic.Theybs all great likenesses by the wat. *especially* Will.

That's not revenge so much as evidence. I hate petty sh*t like this. Since she admitted to the world she destroyed his property it shl0udn&#o39;t be hard to drag her ass to court and sue her for the damage done. Then he can buy a couple of new Nikons to take a picture of the other chick he was likely hotter (saner and more mature) anyway.